Two Outings to the Yuba-American Divide

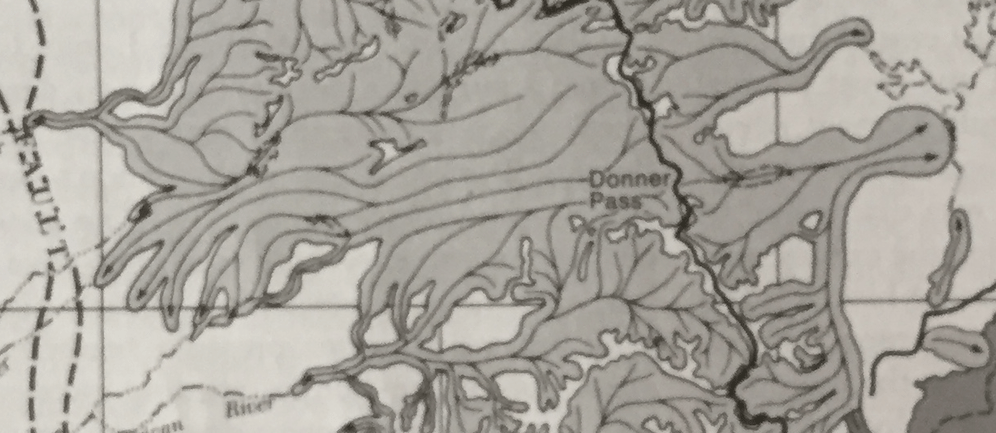

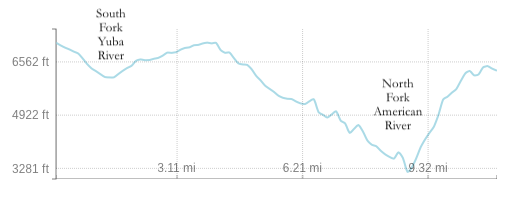

Both the South Fork Yuba and North Fork American drainages have their headwaters against 8 to 9 thousand foot peaks of the Sierra Crest, and both flow roughly parallel to each other to the west. They differ, however, in that the North Fork American is two to three times deeper than the Yuba. One outcome of this was that ancient glaciers filling the upper Yuba basins at various times overrode the divide between the two, creating a section of the divide where large ice falls descended into the deeper American, to join its main glacier far below.

Two recent outings to the divide gave an opportunity to better visualize this unusual topography and the spectacle of massive ice field and long-tongued glaciers that rode down from the summits as recently as 15 thousand years ago.

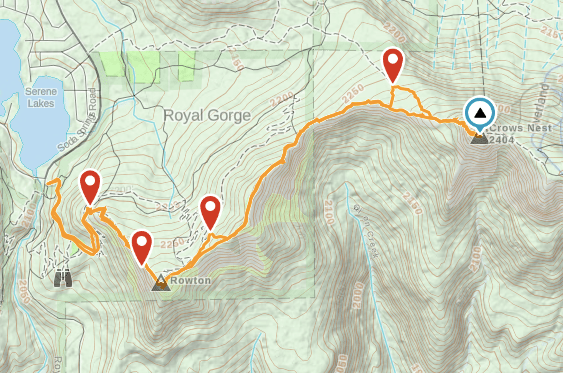

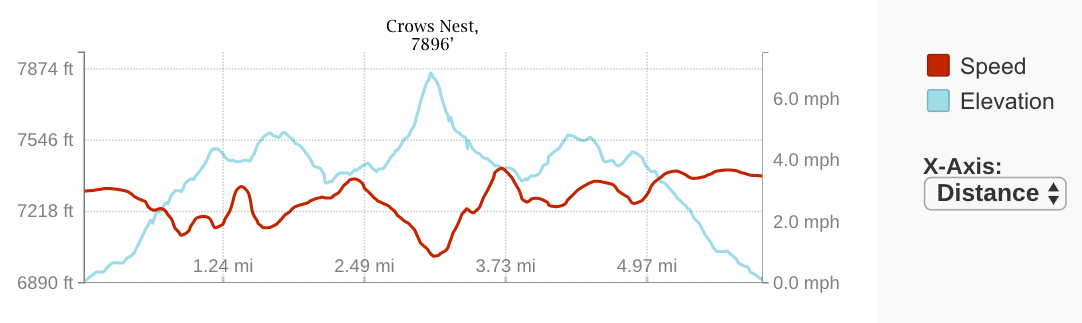

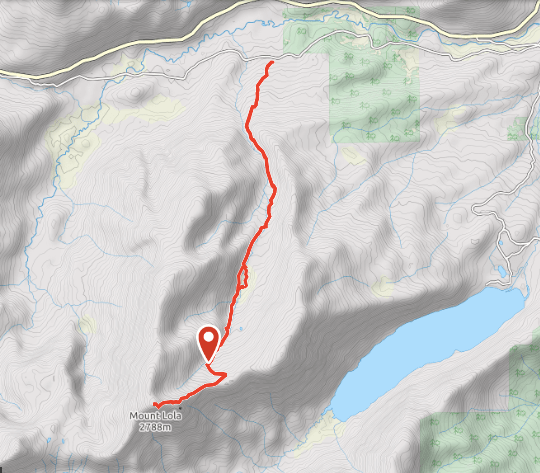

Razorback Ridge to Crows Nest — 17 Nov. 2019, 6 miles return, elevation gain +1,006

The ridge has outstanding views of the headwaters of both the Yuba and America drainages. Andesite, Castle, Donner, Judah and Mt. Lincoln dominate the Yuba, while Anderson, Tinker’s Knob, Granite Chief, Needle and Lyons Peak enclose the American. The ridge itself is composed of recent volcanic layers – ash, welded pyroclastic flows, and the andesite tower of Crow’s Nest. The two faces of the ridge, however, present strongly contrasting features. On the north, where the main ice field of the upper Yuba once covered the shoulders of the ridge to its crown, forest of White and Red Fir, Western White Pine, Sierra Juniper and Mountain Hemlock crowd the slope. Generally just below the ridge top, but sometimes at the top or even down the lee side a few meters are numerous glacial erratics – granodiorite – in striking contrast to the volcanic strata of the ridge itself. Jeffrey pines, in particular stand in exposed locales, often presenting broken tops and wind-sculpted limbs. The south or lee side of the ridge is steeper, mostly barren and deeply eroded into cliffs, ravines, and an irregular series of pillars and other asymmetrical forms carved out of the welded pyroclastic conglomerates. There is even one natural arch. The ascent to Crows Nest is steep only near the end, and the climb up the broken tower itself an easy class 2 scramble.

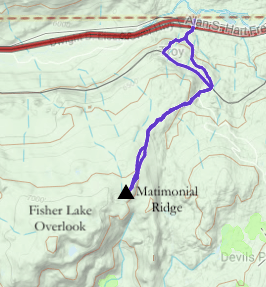

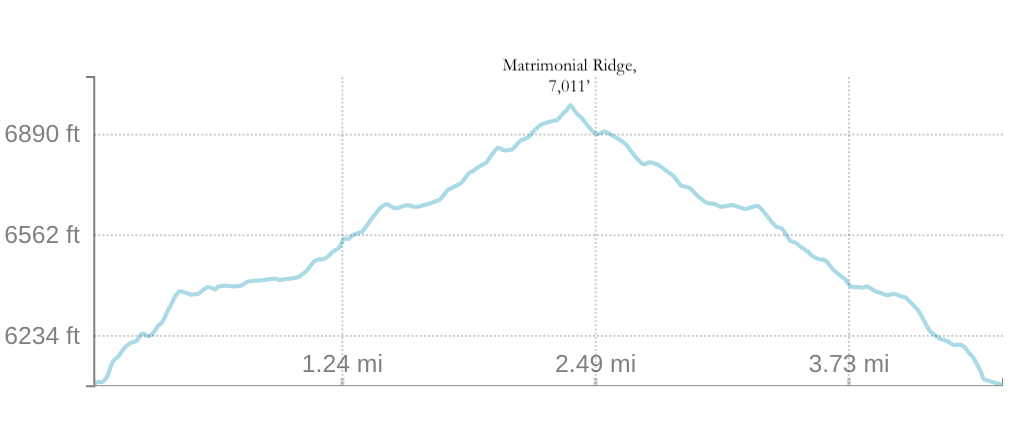

Matrimonial Ridge — 26 Nov. 2019, 4 miles return, elevation gain +971

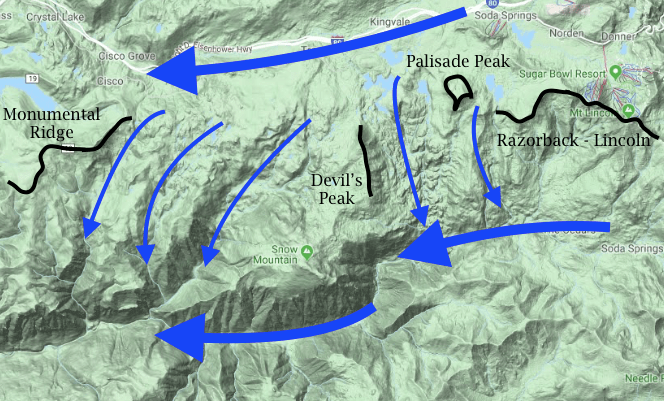

The climb from Hwy 80 and the South Fork of the Yuba River to Matrimonial Ridge is a standard ski, snowshoe or snowmobile route in winter. Without snow it is actually more difficult, with the last roadless, trail-less part of the route dense with forest and crowded with huckleberry oak and manzanita growing between granite ridges and benches. Reaching the first summit of the exposed ridge-top leading to Fisher Lake Overlook, a place informally called ‘Matrimonial Ridge,’ There is polished granite and two solitary Jeffrey Pines. Although overridden by glaciers here at some point, the ridge stands prominently above the landscape so that all of the Granite Creek drainage, once a great ice fall down to the American, can be seen, as well as many of the same peaks of the Yuba and American seen from Razorback Ridge. Nearby is Devil’s Peak, a cockscomb-like ridge composed of columnar andesite that stood above the glaciers and acted as a topological divide between two bodies of ice descending in parallel into the American. Also striking is the uneven terrain on both sides of the divide here. Numerous ridges, hummocks, and benches, all fashioned by the glaciers out of the granite bedrock stretch out across the landscape. It makes for complicated terrain with many small lakes. most of them at the Yuba-American divide, or further down into the American River drainage. Some of these lakes, such as the three Loch Leven Lakes, have trails to them and are popular destinations. Others, such as Nancy or Fisher Lake are cross-country trips and are infrequently visited.

In its large scale, the asymmetry of the two canyons — Yuba and American — is striking. Why was the American cut so much deeper? Did the overriding glaciers from the Yuba icefield contribute to this depth, or was there a pre-glacial reason? The position of the glacial passes between the Yuba and American is also interesting. From the Sierra Crest to Razorback Ridge there are no breaches in the divide between the two. Then, between Razorback Ridge and Monumental Ridge, much to the west, five major drainages cut down into the American, each one being a breach in the divide, with most of the divide in this section continuously overridden at the glacial maximum. Only two prominent features stood above this icy inundation — Palisade Peak just west of Razorback Ridge, and Devil’s Peak, which extends out south to the high wide ridge of Snow Mountain, also glacier-free.

Standing atop Matrimonial or Razorback Ridge one sees clearly how these two watersheds – the Yuba and American — are intimately linked topographically, yet dramatically different.