Tracing the verticality of trees Eye seeking to match Ear's sound cloud to a single voice head back Breast pulsing to the cadence beat A trumpeter whose Repeated call Fills forest with Resound

Walking up the hill trail into neighborhood open space, just out the front door. Empire Mine State Historical Park. Adits and mine shafts underneath. The main mining building complex at lower elevation about a mile away. Second growth forest. At 2,600 to 3,000 feet, Mixed conifer / broad-leaf forest, dominated by Ponderosa Pine and Incense Cedar. Trails old mining roads, just wide enough to ‘physically distance’ in this time of pandemic.

Each morning now I walk as much into pillared, canopied forest with its scents and aerosols, its spring flowerings on the forest floor, its sunrise and morning light filtering through the trees, as into the spring sound cloud of bird song. Winter is more quiet in this forest, an emptiness that allows distant town and road noise to carry over the trees. Now each morning a dawn chorus erupts and I spend my time walking through its complex diversity of call and song. Not a symphony and not a cacophony, its ‘phonics’ is neither orchestrated nor discordant, more a multiphony whose organizer is the diversity of biological niches and the adaptive success of song strategies.

I am no expert. The sound-bathing, though, is therapy is these difficult times of fear, isolation and distancing. I let it wash over me and in moments the individuality of bird call stands out. Today it is the Orange-crowned Warblers, high in the canopy. Spotted towhees give their raspy call in the shrubs or underneath. At various points I hear up-down calls of the Black-headed Grosbeak, quiet ‘tsipt’s of the Juncos, drones of the Bewick’s Wren, distant calls of a Pileated Woodpecker, sweet whistles of the Yellow-Rumped (Audubon’s) warblers that I can follow in the canopy of the Black Oaks, gleaning insects off the emerging leaves and branches.

On the return, following the lower, still-muddy trail, one two-part song arrests me. Like all bird vocalizations it resounds through the trees and I cannot well make out how near or far away is the bird. I scan nearby cedars and ponderosas, then find it suddenly at a lower vista, perched on the top branches, still without leaf, of a Black Oak. At first I hesitate. It is a Dark-eyed Junco, with distinctive dark head. Yet I really only know the Junco from its short, repeated ‘tsipt’ that is so common in Sierra forests. This call is a bell-like, quickly repeated note, deeply resonant and sweet, followed by a second series, slightly lower in pitch, more metallic, almost harsh, yet matched with the first series to give a striking call-out into the trees. I watch carefully, and yes, the bird opens its small bill, pulls back its head, and puffs its breast at the same moment as the bird song again repeats.

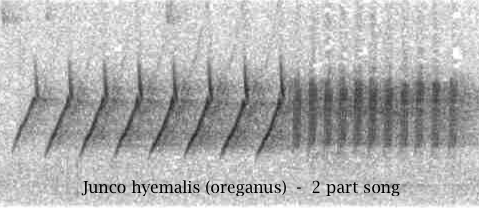

Wonder. For someone familiar this is nothing special perhaps. For me it is a wonder, a scientific ‘discovery’ all the more sweet for its occurrence with such a familiar bird. Peterson’s Field Guide to Bird Sounds gives the visual spectrogram thusly:

And there it is, visually as I heard it — the two part song, the first more bell-like, the second more rattled-metallic. What is most striking upon examination through books and on-line resources is the diversity of vocalization WITHIN one species and with a single bird. There is the distinction between call, song, and alarm. The different sounds have different purposes and meanings. Then within each category there might be variation, particularly within the category of song, which often is meant to attract a mate. More variety is more attractive and more successful. Finally, there is great variation within a population of birds, especially across regions. Just as a Dark-eyed Junco varies greatly in plumage from California to Maine, so also do its vocalizations vary.

This is all part of the greater household in which I move and dwell. To be alive is to be part of a diversity and complexity so vast that it astounds…and welcomes. Should we not feel the more a part of it all for its diversity? We too have our diversity, our uniqueness within commonality, stacked assemblages of organism and event organized through similarity and difference. This is what holds the fabric together, gives it its oneness.

This morning I walk into myself singing the songs I have never heard before, that are my songs Walking beneath trees That are my flesh I laugh To be more tree And bird than me... With reverence I place this little me Like a stone Into a pool And let it join In the great resounding.

7 April 2020 Cedar Wings Cottage

Yes, Gary! Your entry reminds me of a recent tweet from Gary Snyder: “This living flowing land / is all there is, forever / We are it / it sings through us — ” and one of my haiku: “forest bathing / less and less the gap / between us” and so thank you, my friend, for the reminder that we are “all part of the greater household.”

LikeLike

Nice, Victor. Indeed this sense of connection is the common sense of us, little hidden except by our long-practiced human attachment to what feeds or protects our little me. I love that phrase, ‘forest bathing,’ that you use, and its connection to such practices in Japan. Whether it is soap or pine needles, we all need to wash away the barriers that keep us from knowing that greater sense of self. Go take a bath in that beautiful northern forest for me!

LikeLike